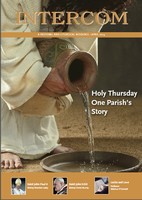

April 2014 issue

April 2014 issue

Click on link to view Intercom April contents

Editorial and Newsletter resources

Feature Article

Lectio and Love by Professor Séamus O’Connell (pdf)

Lectio and Love

When it comes, will it come without warning

Just as I’m picking my nose?

Will it knock on my door in the morning,

Or tread in the bus on my toes?

Will it come like a change in the weather?

Will its greeting be courteous or rough?

Will it alter my life altogether?

O tell me the truth about love.

The apparent lightness, cleverness, and downright poetic genius of W. H. Auden’s O Tell Me the Truth about Love mask the utter seriousness and elusiveness of the question the poet asks. Everybody wants to know the truth about love. Whether we admit it or not, we all hunger for the truth about love.

From Auden to Aquinas

A world away from Auden is Aquinas. Another genius, this medieval theologian and teacher also reflected on the ‘truth about love.’ He arrives at some surprising conclusions. In the Summa (II.23.6) he argues—on the basis of 1 Cor 13:13—for the radical primacy of love: the ‘greatest of these [gifts of the Spirit] is love.’ As a consequence, ‘love attains God himself that it may rest in him, but not that something may accrue to us from him.’ In other words, love is interested in God for God’s sake, to be with God, and not for anything that God may give. To rephrase yet again, love desires God for God’s sake and not for its own.

Desire and Union

While Thomas’s way of arguing may appear a somewhat strange to us, what he is arguing might be very important to us—indeed for any person—if one could we hear him.

Thomas reflects on the character of love: human love is desiring the other—first and foremost—for the sake of the other. This desire for the other—love—brings us into union with the one who is loved, with the beloved: ‘the beloved is, in a manner, in the lover, and, again, the lover is drawn by desire to union with the beloved’ (see Summa Theologiae I-II.66.6). Put another way, love is itself a form of being united with who or what is being loved. To love is already to be within the beloved in some way, and to have the beloved in one’s heart. Truly to love another is somehow to be united with the other. Truly to love another person is already to be united with that person. Truly to love God, is already to be united with God, to be within God, in some way, somehow. To turn to the Song of Songs:

I sought the one whom my soul loves;

I sought him, but I found him not …

… I found him whom my soul loves

I held him and would not let him go … (Song 3:1, 4)

To love the beloved is to seek the beloved. To love God is to seek God. To love God, then, is then not only to seek to ‘serve’ God, but in the first instance, our love of God is expressed in the desire for God. This is what is termed ‘the theological virtue of ‘charity’ by which we love God above all things for his own sake, and our neighbour as ourselves for the love of God.’ (CCC § 1822)

A Lesser God—Seeing the Scriptures as Teaching

Not only do our computers, phones, and televisions have them, but our theologies also have what might be described as ‘default’ settings—ways of seeing things that we assume to be obvious, starting points from which we depart. One of these is that the basic purpose of the Bible is to teach, and to act as repository of the teachings the God wants to pass on to us. In gospel terms, this translates as the core activity of Jesus’ ministry was teaching! This manifests itself in reactions such as,

- ‘The Pharisees didn’t see that the messianic prophecies of the Old Testament applied to Jesus.’

- ‘The disciples didn’t understand Jesus’ teaching on the Kingdom!’

- ‘Jesus told the parables so that people would understand the Kingdom of God.’

The titles and thrust of very venerable books, such as Rudolf Schnackenburg’s The Moral Teaching of the New Testament (which first appeared in 1962), also bolster this view. While there certainly is moral teaching in the New Testament, the New Testament may not be reduced to this. This is a fortiori the case in the parables: they are certainly a feature of the Lord’s teaching, but to reduce them to a type of story with a lesson is seriously to take away their power. The limits of this tenacious approach can be seen when we read this paradigm of understanding and read it some other of life’s situations:

- Mary’s and Jack’s marriage broke down because they didn’t understand their relationship.

- Michael left ministry because he didn’t understand priesthood.

- If people understood the Mass, they’d go more frequently.

Life itself brings most people to see the limits of these (enduring) caricatures: there is more to life and living than understanding. Put in another way, life and living demand another type of understanding. Seeing God’s primary mode of relationship with us as informational is an impoverishment both of God and of the human being. At the heart of the renewed theology of revelation that is the foundation of the Second Vatican Council is that ‘God—in his goodness and wisdom—chose to reveal HIMSELF’ so that we might share not God’s life but that we might be make one with God himself. (Dei Verbum §2) While God remains other, we are made one with God. The word of God—of which the Scriptures are the sacrament—makes us one with God. The Scriptures are much more than a repository for the truth about God and about creation; the Scriptures —opened, engaged with, and welcomed—are the stuff of God’s very life which is offered to us.

Beyond the Message—The Scriptures as School of Desire

Seen in this light, the Bible is a place where God shares his life with us. It is to see that the first approach to the Scriptures is relational and not informational, to adapt an insight of Sandra Schneiders, we read for transformation before we read for information (see The Revelatory Text [2d ed.; Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1999], 13–14).

But how do we read for transformation? Maybe the best answer is that we read for love. We read because we desire the One who speaks to us. To read the Scriptures is to seek the one who speaks: returning to the Song of Songs:

I sought the one whom my soul loves… (Song 3:1)

To read the Scriptures is to seek the one whom we love. In this light, reading the Scriptures, especially by listening in prayer, is listen for the One whom we love and whom we desire. It is this constant desiring that permits us to be changed. We do not and cannot change ourselves (see Romans 7:19–20); it is God who seeks us out and who changes us. Our call is to welcome and respond to what God does within us and for us.

The journey from our conviction that we have our salvation in our grasp to the realization that it is God who saves us is the journey on which Paul brought the Galatians. It is the journey from being under the illusion that the fullness of life is in our grasp to the conviction that life in all its dimensions is a gift: as he says,

For if a law had been given that could make alive, then righteousness would indeed come through the Law (Gal 3:31)

The issue here is that ‘which can make alive,’ that can vivify. For Paul with the Galatians, is not the observance of the Law that makes alive, it is the Holy Spirit, given by what God did in Jesus that make people alive. So it is with us and the Scriptures: it is not the words that make alive—but the word of God, a reality in the Holy Spirit that makes us alive. It is this that we seek.

The Word Comes to Us to OPEN the Heart

The word of God makes us alive. One of the ways of looking at lectio divina is that is a practice of seeking, reflecting upon, chewed, and welcoming God’s word. Lectio can be seen as the disciplined seeking of God’s word and therefore God. It is, to use André Louf’s phrase, a practice of opening the heart towards God. It is a practice of love. To ‘seek God is an absorbing occupation. It comprises all of life and engages the entire person. It is the love of God. To love is already to be within the beloved in some way, and to have the beloved in one’s heart.’[1]

For those of us who are weak, but who in our weakness still seek to love, lectio divina with it discipline and rhythms has proven a structure, a practice a way of the love of God and therefore of our neighbour.

Professor Séamus O’Connell

St Patrick’s College

Maynooth

Intercom

Intercom is a pastoral and liturgical resource magazine published by Veritas, an agency of the Irish Catholic Bishops Commission on Communications.

There are ten issues per year, including double issues for July-August and December-January.

For information on subscribing to Intercom, please contact Ross Delmar (Membership Secretary):

Tel: +353 (0)1 878 8177 Email: [email protected]